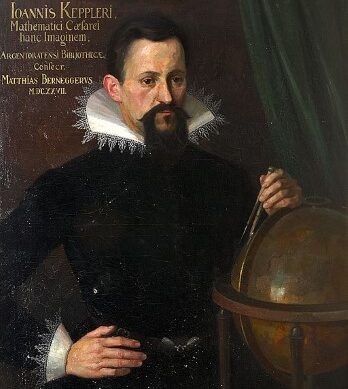

Kepler: An Unlikely Hero

Poverty, health ailments, persecution, government corruption, childhood neglect and trauma: Not exactly prime conditions for forging a great scientist. Yet, these calamities paint the life mural of a man considered to be a father of modern science, particularly astronomy. He discovered supernovas, pioneered in optics, penned revolutionary books and the first work of science fiction, and much more. This man is Johannes Kepler.

Born during the wake of the Protestant Reformation, 1571 was a tumultuous time for any German child to enter the world. For Johannes these times were dwarfed by his home life. The firstborn of a negligent father and distracted mother, he spent his early childhood sick, feeble, and undereducated. When he finally did begin school, however, this blighted beginning did not hinder the brilliant mind trapped in the weak, boyish body. His education, along with two astronomical events that captured his imagination, seem to be the only pleasant childhood memories of this little German.

Disappointment continued to follow him into his first years as a math teacher. Few students attended his first class and those who did found his style flighty and his content laborious to follow. It was worse his second term: not a single student signed up. Surprisingly, the school authorities didn’t place the burden of blame on Kepler for this and allowed him to keep his post, though he did have to begin working as a calendar maker to earn more income.

Eventually, Kepler did gain students again, and it was in the middle of one of his lectures that he had a sudden realization that would change the course of his life– even though his idea would prove to be a laughable blunder. Kepler’s idea was that platonic solids explained the orbit of planets around the sun.

So sure was he of this idea, he wrote a book recording all the math and science he used. While he eventually disproved and corrected this idea, it did provide an initial model of how planets could orbit the sun (a needed feat during a time when heliocentrism was still violently rejected) and gave Kepler a hearing with Europe’s most prominent astronomers at the time. This book also vividly displays– like others he would author– Johannes’ exuberant and unshakable conviction in the God of Genesis and that if God created the world with the order that Genesis records, surely such an order was waiting to be found in the heavens and their laws.

Though excited to research more into the stars, stormy clouds on his nation’s horizon threatened once again to darken Kepler’s life. Mounting Catholic and Protestant conflicts came to a head and the Catholic Archduke ordered all Protestants to leave the province. Almost overnight, Kepler found himself on the run. Through a series of events and aid from friends, Kepler ended up in the service of Tyco Brahe, one of Europe’s best authorities on astronomy. After Brahe’s untimely death, Kepler became his successor, gaining full access to Brahe’s life-time work: careful records and calculations of the heavens. The man who suffered from poor eyesight since childhood, now studied the heavens through another’s eyes.

Sadly, escaping persecution didn’t mean escaping personal loss for Kepler. He lost his wife and little son to illness. Mixed in his grief was much time pleading with the Emperor for the income due him as royal astronomer. Johannes would also live through the Thirty Years War before finally dying of sickness at the age of fifty-eight.

With a life bitter of such personal tragedy, how could anyone emerge not only a strong, cheerful Christian, but possibly the most remembered and revered scientist of the past four centuries? Dr. Henry Morris has succinctly summed up Kepler’s numerous accomplishments, “[He] is considered to be the founder of physical astronomy…it was he who discovered the laws of planetary motion and who established the discipline of celestial mechanics. He conclusively demonstrated the heliocentricity of the solar system and published the first ephemeris tables for tracking star motions, contributing also to the eventual development of the calculus.”

What made Johannes such an amazing man and scientist, was his biblical faith. In defiance to the popular beliefs of his day, which saw chaos in the heavens and feared them as sources for doom, and superstition, Kepler saw sense, order, and beauty in the creation he studied. Kepler believed the Bible’s chronology and sought to bring glory to God in his work. Perhaps the greatest achievement of his life is shifting Western science from guesswork based on ancient superstition, to an orderly, logic based discipline that presupposed an orderly, logical Creator– the Creator of the Bible.